9/30/2006

Het boek der boeken en het geweten

Het onderstaande is een tekst uit een interview met Levinas genaamd “De vreemdeling liefhebben”, door François Poirié, uit het boek: “Emmanuel Levinas aan het woord – 11 gesprekken” (2006). Hij beschrijft een bijbelvers als illustratie van waarom hij het niet altijd eens is met Martin Buber - Buber is net als Levinas een Joodse filosoof, en hij schrijft ook over de relatie tussen de één en de ander.

Het onderstaande is een tekst uit een interview met Levinas genaamd “De vreemdeling liefhebben”, door François Poirié, uit het boek: “Emmanuel Levinas aan het woord – 11 gesprekken” (2006). Hij beschrijft een bijbelvers als illustratie van waarom hij het niet altijd eens is met Martin Buber - Buber is net als Levinas een Joodse filosoof, en hij schrijft ook over de relatie tussen de één en de ander.Levinas heeft een heel boeiend maar ook een heel moeilijk voorbeeld gekozen om te laten zien hoe hij met Buber van mening verschilt. Eigenlijk heeft hij het zichzelf hiermee moeilijk gemaakt, omdat veel mensen geneigd zullen zijn Buber gelijk te geven. Maar dat vind ik dan ook juist weer heel mooi van Levinas, dat hij zo’n moeilijk voorbeeld uitkiest.

Citaat van Levinas:

Ik zal u iets vertellen over een passage die ik onlangs gelezen heb, waarin Buber me erg verrast heeft. Een tekst van Buber die betrekking heeft op zijn eigen leven. Hij ontmoet een oude, heel vrome jood die hem een vraag stelt over Samuel, 15, 33 vers 1, waarin de profeet het beveel geeft aan koning Saul om het koninkrijk Amalek, dat in de bijbeltraditie en de talmoedische het radicale kwaad belichaamt, van de kaart te vegen en uit de geschiedenis te wissen. Amalek had op een laffe wijze de Israëlieten aangevallen die uit Egypte kwamen, slaven die nog maar net bevrijd waren. Laten we niet over de geschiedenis of de feiten discussiëren. De betekenis van de bijbelse hyperbolen moet je zoeken in de contexten van die hyperbolen, zelfs als de verzen ver van elkaar staan!

In Deuteronomium 25, 12:

“Wanneer de Eeuwige, jouw God, je verlost zal hebben van alle vijanden in het land dat hij je geeft… zul je de herinnering aan Amalek onder de hemel uitwissen.”

De mens die van het kwade verlost is, moet de ultieme slag aan het kwade toedienen. Saul vervult zijn plicht niet. Hij kan niet uitwissen. Hij spaart Agag van Amalek en brengt een buit mee, de beste dieren uit de kuddes van Amalek. De scene waarin de profeet Samuel rekenschap vraagt. Dialoog:

- 'Wat is dat gemekker aan mijn oren en dat geloei van de runderen?'

- 'Die zijn om te offeren aan de Eeuwige, jouw God.'

- 'De Eeuwige houdt niet van brandoffers, hij heeft graag dat men zijn stem gehoorzaamt. Breng koning Agag.'

Antwoord van Buber: de profeet heeft niet begrepen wat God hem bevolen heeft. Buber dacht waarschijnlijk dat zijn geweten hem beter inlichtte dan de boeken over de wil van God! En waarom heeft hij in Samuel, 15, 33-1 het woord van de profeet niet gelezen: ‘Zoals uw zwaard de vrouwen van hun kinderen beroofd heeft, zo zal uw moeder van haar kinderen beroofd worden onder de vrouwen.’

Ik ben het niet altijd eens met Buber, ik heb het u gezegd. Ik blijf denken dat je zonder uiterste aandacht voor het boek der boeken niet naar het geweten kan luisteren. Buber heeft in dit geval niet aan Auschwitz gedacht.

Als je deze tekst vanuit een buiten-religieus perspectief leest, dan ben je veel eerder geneigd Buber gelijk te geven. Een volk uitroeien, een land van de kaart vegen, hoe kan dat nu het bevel zijn van een goede God, om allemaal onschuldige mensen, vrouwen, kinderen en baby’s dood te maken, dat kan toch nooit de bedoeling zijn. Dan kun je beter wat schapen offeren. De profeet zal het wel verkeerd begrepen hebben. De terroristen van nu zijn er ook heilig van overtuigd dat het Gods bevel is om onschuldige mensen uit te roeien, maar wij weten wel beter. Dus het is altijd verstandig om eerst je gezonde verstand en geweten te gebruiken, en niet zomaar een “bevel van God” op te volgen als je zelf denkt dat dat helemaal niet goed is.

Levinas kijkt hier echter heel anders tegenaan, een perspectief dat van binnenuit de religie komt. Als gelovige zijn er enkele aannames die niet ter discussie staan. Dat God bestaat, staat niet ter discussie. Dat God goed is, staat ook niet ter discussie. Het is onmogelijk dat God een kwaadwillende duivel blijkt te zijn. Deze aannames zitten heel diep, zij worden aangenomen al voordat een gelovige daar bewust over nagedacht heeft. In feite heeft iedere mens voorafgaand aan ieder bewustzijn een besef dat God bestaat en dat God goed is. Daarna gaan mensen daar past bewust over nadenken en een bepaalde religie volgen (of ze worden atheïst).

God is oneindige Goedheid en niets anders dan goedheid, het kwaad is totaal afwezig in hem. God roept de mens nog voordat de mens geboren is. Voordat er een bewustzijn ontwikkeld is, is de mens al geroepen en heeft de mens al gehoor gegeven aan de oproep. Levinas schreef niet alleen filosofische werken maar ook Talmoedische studies. In zijn “Vier Talmoedische studies” schrijft hij over toen de Joden de Thora kregen op de berg Sinaï, zij zeiden toen: “wij zullen doen en wij zullen horen”. In het begin heeft God een verdrag gesloten met zijn volk. En het volk heeft gezegd dat zij zullen doen en dat zij zullen horen. Een verdrag dat voorafgaat aan keuzevrijheid en de rede, maar waarbij er ook geen sprake is van dwang. Ik schreef al eerder over het “wij zullen doen en wij zullen horen”. Zoals ik toen al zei, betekent die zin dat de steun van de Joden aan God onvoorwaardelijk is. Er is geen afweging van voor- en nadelen, geen rationele keuze om wel of geen gehoor te geven aan de oproep van God. Dit is de kern van onvoorwaardelijke aanvaarding: eerst te doen en dan pas te horen of te denken. De omkering van de normale volgorde - eerst denken en dan doen - is een vorm van handelen die niet op onwetendheid gebaseerd is maar op een weten waar geen calculatie aan te pas komt.

Vanuit het buiten-religieuze perspectief klinkt dit allemaal heel vreemd, hoe kan God nu een verdrag met mij hebben gesloten terwijl ik daar niet bij was (leuk dat mensen op de berg Sinaï dat hebben gezegd maar wat heb ik daarmee te maken), hoe kan ik iets aanvaard hebben zonder een bewustzijn, zonder dat ik gekozen heb? En waarom zou ik zomaar een bevel van iemand uitvoeren terwijl ik helemaal niet weet waarom hij vindt dat ik dat moet doen, en terwijl ik zelf vind dat het heel slecht is om dat te doen. Eerst doen en dan pas horen en denken, is het niet veel verstandiger om eerst te denken, voordat je iets heel verkeerds gaat doen. Blind bevelen opvolgen kan heel gevaarlijk zijn, en je bent toch in de eerste plaats verantwoordelijk voor je eigen daden. Het kan nooit goed zijn om een volk uit te roeien, als ik zoiets doe kan ik mijn verantwoordelijkheid nooit afkopen door te zeggen dat het een bevel van God was, ik ben nog steeds verantwoordelijk voor de schade die ik anderen berokken.

Maar dat is volgens Levinas het hele idee van onvoorwaardelijke aanvaarding, dat je ja zegt zonder dat je weet waar je ja tegen zegt, of waarom, zelfs zonder dat je je bewust bent van het ja zeggen (nee zeggen was geen bewuste optie). Dit is ook hoe het gaat wanneer de ander mij aanspreekt, die een schok te weeg brengt waarin God in me opkomt. Het beroep dat de ander op mij doet is het woord van God, dat de volharding in mijn zijn (mijn geïsoleerde egoïsme) omkeert in de toewijding voor de ander. Die schok gaat vooraf aan mijn bewustzijn. Dus het is niet zo dat iemand mij aanspreekt en dat ik bewust denk: zal ik antwoorden of zal ik doorlopen zonder iets te zeggen, ik heb nogal haast eigenlijk, geen zin om moeite te doen, laat maar zitten die ander. Nee, iemand roept me en ik kijk om zonder er bij na te denken. Ik geef gehoor aan de oproep van de ander door te doen, onvoorwaardelijk.

Maar dat is volgens Levinas het hele idee van onvoorwaardelijke aanvaarding, dat je ja zegt zonder dat je weet waar je ja tegen zegt, of waarom, zelfs zonder dat je je bewust bent van het ja zeggen (nee zeggen was geen bewuste optie). Dit is ook hoe het gaat wanneer de ander mij aanspreekt, die een schok te weeg brengt waarin God in me opkomt. Het beroep dat de ander op mij doet is het woord van God, dat de volharding in mijn zijn (mijn geïsoleerde egoïsme) omkeert in de toewijding voor de ander. Die schok gaat vooraf aan mijn bewustzijn. Dus het is niet zo dat iemand mij aanspreekt en dat ik bewust denk: zal ik antwoorden of zal ik doorlopen zonder iets te zeggen, ik heb nogal haast eigenlijk, geen zin om moeite te doen, laat maar zitten die ander. Nee, iemand roept me en ik kijk om zonder er bij na te denken. Ik geef gehoor aan de oproep van de ander door te doen, onvoorwaardelijk.Het is volgens Levinas niet gevaarlijk om onvoorwaardelijk gehoor te geven aan de oproep van God, want een wezen dat totale oneindige goedheid is, zal nooit een slecht, gemeen, onrechtvaardig bevel geven. Dit is een logisch gevolg van de aanname dat God oneindige goedheid is, een aanname die voor Levinas als gelovige niet ter discussie staat.

Laten we nu teruggaan naar het voorbeeld van Samuel en Saul. De bijbel is geen kookboek dat letterlijk opgevolgd moet worden - men neme deze ingrediënten en men doet er dat mee. Zo van, in de bijbel staat: “Wanneer de Eeuwige, jouw God, je verlost zal hebben van alle vijanden in het land dat hij je geeft… zul je de herinnering aan Amalek onder de hemel uitwissen.” (het citaat dat Levinas in het voorbeeld zelf noemde). Dat het dan geïnterpreteerd wordt van: Laten we nu kijken wie de vijand van de Joden is in het land dat zij van God hebben gekregen, en laten we dat volk (Palestijnen) dan gaan uitroeien, want dat staat in de bijbel. Dat is nadrukkelijk niet de bedoeling. De bijbel als ethische gids moet op een hele andere manier gelezen worden. Levinas zegt nadrukkelijk dat we niet over de geschiedenis of de feiten moeten gaan discussiëren. Het gaat niet om de vraag of het rechtvaardig was dat Samuel Agag doodde of dat God een bevel gaf tot uitroeiing van een volk. Voor Levinas is een bijbelvers een soort ethische puzzel, een oefening in het begrijpen van de tekst als een boodschap van God over hoe wij mensen op aarde met elkaar om moeten gaan. Daarom is het belangrijk om die boodschap goed te interpreteren. Het is vooral daarom dat Levinas zich richt op Talmoedische studies, om niet alleen de tekst van de bijbel zelf te lezen maar veel aandacht te besteden aan de juiste interpretatie daarvan, door te lezen wat Joodse wijzen daar in de loop der geschiedenis over geschreven hebben.

Het beginpunt is dat God goed is, en dat de profeten goed zijn. Als je die twee ideeën voor waar aanneemt, dan is Bubers interpretatie van het voorbeeld, dat de profeet zich vergist heeft en het bevel van God verkeerd begrepen heeft, niet erg voor de hand liggend. De manier waarop het verhaal in de bijbel is opgeschreven, draagt niet de boodschap uit dat Samuel dom is, dat hij ten onrechte dacht dat God zoiets gruwelijks als bevel aan Samuel/Saul gaf. De bijbeltekst wekt sterk de indruk dat het wel het bevel van God zelf was dat Amalek van de kaart geveegd / onder de hemel uitgewist moest worden.

Als God alleen maar hele redelijke, goed te begrijpen, volledig te steunen, makkelijk uit te voeren opdrachten geeft, dan is het niet zo moeilijk voor het Joodse volk om te zeggen: “Wij zullen doen en wij zullen horen.” Pas als de eis onbegrijpelijk en onmogelijk is, dan wordt er echt iets gevraagd qua onvoorwaardelijke aanvaarding. Een ander voorbeeld hiervan is de opdracht van God aan Abraham dat hij zijn geliefde zoon Isaäk moest offeren. De opdracht die God geeft is vreselijk. Alles in Abraham, zijn gezonde verstand, zijn geweten, zijn liefde voor zijn zoon, alles zegt hem dat hij zijn zoon niet kan offeren. God kan heel veel van hem vragen maar dat niet. Toch besluit Abraham gehoor te geven aan het bevel van God. Vanuit een buiten-religieus perspectief zou je zeggen dat die Abraham knettergek is. Je gaat je eigen zoon toch niet vermoorden omdat die gekke god van jou dat bevel geeft. Die God zoekt het maar uit, dat soort bevelen moet je nooit opvolgen. En hoe kan een goede God nu zo’n bevel geven. Maar Abraham gehoorzaamt onvoorwaardelijk, hij vertrouwt erop dat God het het beste met hem voor heeft, ook al begrijpt hij totaal niet hoe God dan zo’n bevel kan geven. Het fijne van dit voorbeeld in vergelijking tot het voorbeeld van Samuel en Saul, is dat Isaäk nog in levende lijve is aan het eind van het verhaal, als God Isaäk echt dood had laten maken was het toch een wat minder prettige les over gehoorzaamheid geweest. Daarom is het voorbeeld van Samuel een heel stuk luguberder.

Als God alleen maar hele redelijke, goed te begrijpen, volledig te steunen, makkelijk uit te voeren opdrachten geeft, dan is het niet zo moeilijk voor het Joodse volk om te zeggen: “Wij zullen doen en wij zullen horen.” Pas als de eis onbegrijpelijk en onmogelijk is, dan wordt er echt iets gevraagd qua onvoorwaardelijke aanvaarding. Een ander voorbeeld hiervan is de opdracht van God aan Abraham dat hij zijn geliefde zoon Isaäk moest offeren. De opdracht die God geeft is vreselijk. Alles in Abraham, zijn gezonde verstand, zijn geweten, zijn liefde voor zijn zoon, alles zegt hem dat hij zijn zoon niet kan offeren. God kan heel veel van hem vragen maar dat niet. Toch besluit Abraham gehoor te geven aan het bevel van God. Vanuit een buiten-religieus perspectief zou je zeggen dat die Abraham knettergek is. Je gaat je eigen zoon toch niet vermoorden omdat die gekke god van jou dat bevel geeft. Die God zoekt het maar uit, dat soort bevelen moet je nooit opvolgen. En hoe kan een goede God nu zo’n bevel geven. Maar Abraham gehoorzaamt onvoorwaardelijk, hij vertrouwt erop dat God het het beste met hem voor heeft, ook al begrijpt hij totaal niet hoe God dan zo’n bevel kan geven. Het fijne van dit voorbeeld in vergelijking tot het voorbeeld van Samuel en Saul, is dat Isaäk nog in levende lijve is aan het eind van het verhaal, als God Isaäk echt dood had laten maken was het toch een wat minder prettige les over gehoorzaamheid geweest. Daarom is het voorbeeld van Samuel een heel stuk luguberder.De bijbelse lessen van onvoorwaardelijke gehoorzaamheid lijken voor een buiten-religieus perspectief nogal dogmatisch te zijn. Zo van: ik ben de almachtige God, ik ben hier de baas, en jullie moeten blindelings gehoorzamen, niet zelf nadenken, niet protesteren, gewoon altijd precies doen wat ik zeg, anders zwaait er wat. Maar Levinas is zelf helemaal geen dogmatisch denker, en dit is niet hoe hij de bijbelteksten interpreteert. Het gaat dus veel meer om een verdrag dat een oneindig goede God met zijn mensen heeft gesloten, nog voordat zij een bewustzijn hadden. Dus de mensen kunnen God vertrouwen, altijd, zij kunnen God onvoorwaardelijk steunen, en God zal hen onvoorwaardelijk steunen, hen nooit in de steek laten. Goed te doen is God volgen, en omgekeerd. Wij zullen doen betekent: wij zullen goed doen. En Gods woord bereikt mij via de het gelaat van de ander dat een beroep op mij doet. De conclusie is dat zelfs als het bevel van God volledig tegen mijn geweten in gaat, tegen mijn redelijkheid, mijn normen en waarden, mijn gevoel voor rechtvaardigheid, zelfs als ik het onmogelijk over mijn hart kan verkrijgen om te doen wat God zegt, dan nog kan ik onvoorwaardelijk op hem vertrouwen, dan nog is mijn aanvaarding onvoorwaardelijk.

Dus het antwoord op de vraag: Hoe heeft Samuel dat kunnen doen, Arag vermoorden? is voor Levinas ongeveer: God gaf Samuel een opdracht en Samuel heeft die opdracht onvoorwaardelijk geaccepteerd. Niet omdat je blindelings moet gehoorzamen aan iemand die hoger staat op de hiërarchische ladder, niet omdat Samuel zichzelf te dom vindt om zelf te oordelen, nee, alleen omdat zijn geloof en vertrouwen in de God van oneindige goedheid onvoorwaardelijk is. Dus Samuel heeft het helemaal niet verkeerd begrepen, die heeft het juist heel goed begrepen. Levinas zegt dat Buber denkt dat zijn geweten hem beter inlicht over de wil van God dan de boeken. Dat kan natuurlijk niet. We moeten niet beginnen met zelf denken, we moeten beginnen met lezen in de bijbel. Voor gelovigen moet de aanvaarding van God onvoorwaardelijk zijn. In de bijbel staat het woord van God. Laten we dat lezen en proberen te begrijpen wat er in de bijbel staat, dat is de enige manier voor een gelovige, tenminste als je net als de Joden op de Sinaï berg wilt zeggen: wij zullen doen en wij zullen horen. Daarom zegt Levinas: “Ik blijf denken dat je zonder uiterste aandacht voor het boek der boeken niet naar het geweten kunt luisteren.

9/19/2006

De ander dat ben jij

Het onderstaande is een tekst die ik voor de website Wij blijven hier heb geschreven naar aanleiding van het debat waar ik vanavond heen was.

Het onderstaande is een tekst die ik voor de website Wij blijven hier heb geschreven naar aanleiding van het debat waar ik vanavond heen was.De titel van het debat van en van de vredesweek “De ander dat ben jij” sprak me meteen aan toen ik de aankondiging op de website van Pax Christi zag. Ik ben gefocust op het concept van “de ander” omdat ik een proefschrift schrijf over een filosoof die de relatie met de ander heeft onderzocht: Emmanuel Levinas. En het doel van mijn proefschrift is om zijn analyse toe te passen op intercultureel contact, dus daar sloot het onderwerp van het debat heel mooi bij aan. Het debat was boeiend – vooral wat Umar Mirza zei, waardoor ik benieuwd werd naar de website www.wijblijvenhier.nl – maar het had naar mijn mening nog wel wat dieper tot de kern kunnen doorgaan.

Josine Blok (professor Oude Geschiedenis Universiteit Utrecht) zei dat verschillen benoemen enerzijds noodzakelijk is en anderzijds gevaarlijk, en dat daartussen een flinterdunne lijn loopt. Maar ik denk eigenlijk dat die lijn niet zo dun is, dat het duidelijk te zien is waar en waarom het gevaarlijk wordt en waar het juist goed is.

Wel verschillen onderkennen en accepteren maar geen vijandig wij-zij denken, dat is volgens mij heel goed mogelijk in de praktijk en ook erg nodig.

Levinas zegt twee dingen:

- De ander is totaal anders dan ik.

- Ik ben verantwoordelijk voor de ander.

Levinas schrijft niet speciaal over autochtonen versus allochtonen, de ander hoeft helemaal geen “vreemdeling” te zijn met een totaal andere cultuur /geloof. Iedere andere mens is totaal anders dan ik. We kunnen best op elkaar lijken en veel gemeenschappelijk hebben, maar ik moet niet denken dat de ander en ik hetzelfde zijn, we zijn niet inwisselbaar. Ik kan niet de gedachten denken van de ander, ik kan niet in zijn schoenen gaan staan en ik mag dat ook nooit pretenderen. Ik mag de ander geen woorden in de mond leggen, niet in zijn naam spreken, niet denken dat ik hem 100% doorgrond. Ik ga niet over de ander, ik ga alleen over mezelf. Als ik iets zeg over de ander dan is dat bepaald door hoe IK kijk naar de wereld en naar de ander, mijn persoonlijke subjectieve perspectief. Ik beoordeel het uiterlijk van de ander, ik vorm me een beeld, ik schat hem of haar in als een bepaald type persoon. Vanuit mijn gekleurde bril beschrijf ik hoe ik de ander zie. Maar de kleur van mijn bril hoort bij mij, niet bij de ander. Met een andere kleur bril krijgt het beeld van die persoon een andere kleur. Alle mensen hebben vooroordelen. We kijken niet alleen naar de mensen die we om ons heen zien maar we interpreteren ook wat we zien, we maken een inschatting, we delen mensen in categorieën in, we oordelen over hen. Als we dat niet zouden doen zou de wereld totaal onbegrijpelijk voor ons zijn, met zoveel details waar we geen lijn in zien. Maar de kleur van mijn bril (mijn persoonlijke achtergrond, normen en waarden, oordelen) zit in mij en hoort niet bij de ander. Ik mag de ander geen stickers opplakken van “jij bent typisch een zo en zo iemand”. Er zijn geen typische mensen, alleen unieke individuen.

Als we precies hetzelfde zouden zijn, dan zou ik de ander kunnen kennen zoals ik mijzelf ken, dan zou ik kunnen zeggen wat de ander vindt zoals ik zelf kan zeggen wat ik vind. Dan zou ik uitspraken kunnen doen over hoe de ander in wezen is. Maar daarmee pin ik de ander vast op mijn oordeel over hem of haar. Dat mag ik niet doen. We blijven altijd gescheiden, we worden nooit een en dezelfde. De ander gaat over zichzelf en spreekt voor zichzelf en ik spreek voor mezelf, niet voor de ander.

Een voorbeeld:

Iemand uit de zaal zei: "Als ik vrouwen met een hoofddoek zie dan wil ik iets doen tegen hoe zij onderdrukt worden". Als zij een vrouw met een hoofddoek ziet, is haar interpretatie daarbij: die vrouw wordt onderdrukt. Dat is haar interpretatie, haar beeld van “vrouwen met een hoofddoek”. Iedere vrouw met een hoofddoek plakt zij de sticker op van onderdrukte. Aan de vrouw zelf wordt niets gevraagd, ze wordt beoordeeld op basis van haar hoofddoek. Door de manier waarop de kijker kijkt, de kleur van de bril, wordt een hoofddoek direct verbonden aan onderdrukking, en dat geldt dan voor alle vrouwen met een hoofddoek. Terwijl er hele grote verschillen kunnen zijn in de redenen waarom vrouwen een hoofddoek dragen en hoe hun positie is ten opzichte van bijvoorbeeld mannen in hun omgeving. Ik moet de ander geen stickers opplakken maar de ander voor zichzelf laten spreken. In plaats van dat ik ga verzinnen wat het betekent dat de ander een hoofddoek draagt, kan ik de ander ook vragen waarom die een hoofddoek draagt.

En het tweede punt is dus dat ik verantwoordelijk ben voor hoe ik de ander behandel. Als ik helemaal alleen ben dan kan ik doen waar ik zin in heb, dan kan ik puur egoïstisch zijn en dan hoef ik met niemand rekening te houden. Maar zodra ik een ander ontmoet moet ik met die ander rekening houden. Ik mag een individu niet reduceren tot een categorie, tot onderdeel van een groep met bepaalde eigenschappen. Er bestaan groepen met eigenschappen maar daarbinnen zijn er individuen die allemaal anders zijn. Dat iemand tot een bepaalde groep behoort betekent niet dat ik het individu kan vastpinnen op de eigenschappen van de groep. Ik kan niet zeggen: “oh daar heb je weer zo’n … (kutmarokkaan / rechtse bal / dom vrouwtje), ik ken jouw soort”. Ik herhaal: er zijn geen soorten mensen, alleen unieke individuen.

Als ik de ander in een hokje stop, als ik hem reduceer tot een categorie met bepaalde eigenschappen, als ik discrimineer, als ik de ander monddood maak, dan behandel ik de ander onmenselijk, dan behandel ik hem als een ding waarmee ik kan doen wat ik wil, in plaats van als een gelijkwaardig mens. Zodra ik een andere mens ontmoet is onze relatie ethisch. Stel dat iemand aan het verdrinken is en mij vraagt hem te redden. Als ik dat dan weiger, terwijl ik het wel zou kunnen doen, dan ben ik er verantwoordelijk voor als de ander verdrinkt. Ik heb de plicht de ander te helpen zoveel ik kan. Ik heb de plicht de ander als gelijkwaardig mens te behandelen en te luisteren naar wat de ander zegt. Ik heb de plicht de ander menselijk te behandelen in plaats van onmenselijk (met vooroordelen, discriminatie, racisme).

De ander heeft die plicht ook naar mij toe, maar dat is dan aan hem of haar. Het gaat altijd om mijn plicht naar de ander toe, niet om dat ik de ander vertel wat die moet doen.

Nog een voorbeeld als toelichting: Wanneer autochtonen roepen dat allochtonen zich meer moeten aanpassen, dan zou Levinas daarop zeggen dat hij dat een verkeerd uitgangspunt vindt. Een autochtoon zou zich in de eerste plaats moeten afvragen: Wat doe ik voor de ander, een allochtoon? Bied ik de vreemdeling een gastvrije ontvangst, ben ik tolerant en verdraagzaam, zoals dat mijn plicht is als autochtoon? En de allochtoon zou zichzelf dan moeten afvragen: Hoe gedraag ik mij als gast, hoe behandel ik de ander, een autochtoon, die mijn gastheer is, houd ik rekening met wat hier gebruikelijk is, gedraag ik mij netjes op de plek waar ik te gast ben? En natuurlijk zijn er grenzen aan de gastvrijheid en grenzen aan de aanpassing, en die zijn ook afhankelijk van hoe de ander zich gedraagt. Maar het beginpunt is mijn verantwoordelijkheid voor de ander.

Dus tegen iedereen die ik ontmoet kan en moet ik zeggen: “De ander dat ben jij, en ik zal rekening met jou houden, ik neem de verantwoordelijkheid op me om jou als gelijkwaardig mens te behandelen, ongeacht waar je vandaan komt, wat je geloof is, wat je gewoontes, je overtuigingen zijn. Jij bent totaal anders dan ik, ik sta klaar om te luisteren naar wat jij te zeggen hebt, ik wil je leren kennen en proberen je te begrijpen.”

9/17/2006

Plea for humanity

Below is a text I wrote for Orkut. I am the moderator of the discussion group International Relations, with almost 12.000 members. The last days there were many fights again between India and Pakistan and Muslims and non-Muslims (sometimes Hindu's). Somebody proposed that we should talk about some other topics to calm things down, like people to people exchanges. Then I decided to write a text about my experience with youth exchanges:

Below is a text I wrote for Orkut. I am the moderator of the discussion group International Relations, with almost 12.000 members. The last days there were many fights again between India and Pakistan and Muslims and non-Muslims (sometimes Hindu's). Somebody proposed that we should talk about some other topics to calm things down, like people to people exchanges. Then I decided to write a text about my experience with youth exchanges: I have been organising and taking part in cultural youth exchanges for the past 14 years, mostly as a volunteer. I would like to talk about my experiences and the effectiveness of youth exchanges in improving intercultural contact. A youth exchange usually takes 2 or 3 weeks, with 8-25 participants from 4 to 10 countries mostly in Europe but also from countries like Mexico, Japan, Korea, Ghana, India. The youngsters do voluntary work, they go on excursions, and they do intercultural activities like making music together, playing games and having discussions.

In general I think that it works very well to organise youth exchanges, it helps to take away prejudices and usually the youngsters learn a lot about themselves and about others and their cultures. I think direct contact is a very important factor in taking away prejudices and negative emotions / images of certain cultural, ethnic or religious groups. The most important effect is that people meet other people concretely, they meet unique individuals, as opposed to thinking about abstract general categories. Individuals never completely fit into the invented image of the group they belong too, since every individual is different so you would need an infinite number of categories for that, just as many as there are individual persons in the world.

In general I think that it works very well to organise youth exchanges, it helps to take away prejudices and usually the youngsters learn a lot about themselves and about others and their cultures. I think direct contact is a very important factor in taking away prejudices and negative emotions / images of certain cultural, ethnic or religious groups. The most important effect is that people meet other people concretely, they meet unique individuals, as opposed to thinking about abstract general categories. Individuals never completely fit into the invented image of the group they belong too, since every individual is different so you would need an infinite number of categories for that, just as many as there are individual persons in the world.There is a kind of a paradox in this that cultural youth exchanges also lead to the creation of new prejudices and stereotypes. You meet only one or two persons from a certain country and you could start to think that everybody over there will be like that. I heard another volunteer say that because of having participated in many exchanges now, he created more images in his head of “typical Spanish youth” as opposed to the French, Polish, Moroccans, etc., based on his personal experiences with volunteers from the different countries. He wondered if these exchanges had a negative effect then, if it leads to more stereotyped thinking. But I think that the images about other cultures that this volunteer got now, are better than the ones people have before taking part in youth exchanges. The new images are based on face to face contact with concrete people. The images contain factual knowledge about other cultures. And the images will not only be negative, they will be balanced, since the volunteer meets both nice people and people he dislikes from many different countries. If he dislikes people from a certain country more often than he probably just doesn’t like that culture. Of course when you meet some random people from a certain country in a youth exchange, you should not think that everybody from that country is like that.

In my opinion it would be good if the leaders of a youth exchange deliberately focus on intercultural learning and decreasing simplistic stereotyped thinking about other cultures. Images based on abstract ideas have a bigger chance of being biased, simplified and negative than images based on concrete contact. But the last ones are not automatically realistic. It is also possible that the exchange becomes a negative experience in which the frustrations / hatred that somebody felt for another culture only gets deeper. If you want to have fruitful intercultural contact then all participants should have enough intercultural skills to have a constructive cultural exchange.

In my opinion it would be good if the leaders of a youth exchange deliberately focus on intercultural learning and decreasing simplistic stereotyped thinking about other cultures. Images based on abstract ideas have a bigger chance of being biased, simplified and negative than images based on concrete contact. But the last ones are not automatically realistic. It is also possible that the exchange becomes a negative experience in which the frustrations / hatred that somebody felt for another culture only gets deeper. If you want to have fruitful intercultural contact then all participants should have enough intercultural skills to have a constructive cultural exchange.These are skills / an attitude like:

- Accept that the other is totally different

- Be able to really listen without judging too fast, without an interpretation from your own perspective

- Open-mindedness

- Show empathy and respect for the other

- Try to put yourself in the shoes of the other

- Ask questions if you are not sure if you understood the other correctly

- Be patient

- Be flexible and improvise, try different ways to understand each other better

- Show that you consider the other to be completely equal to you

- Don’t start projecting your own images of the other onto the other

- Don’t reduce an individual to the characteristics of a group

So the idea of a youth exchange is not only that young people from different countries meet each other and that they make new friends and that prejudices and stereotyped thinking decrease in an informal way. The idea is also that the leaders teach the participants intercultural skills and that the youth practice these skills during the exchange. When the intercultural learning is both formally and informally then it will be the most effective.

When we compare youth exchanges to intercultural contact at Orkut, I think that there are two major differences:

- There is no direct contact in the offline physical world at Orkut. The other presents him or herself to me with a picture and a typed description. It is more difficult to always realise that the people who are posting their profiles on Orkut and who are taking part in the discussions, that they are real people, they could be my colleagues at my work, my friends, the owners of the shops where I buy my food, etc. (although they might live at the other side of this world). With the people I meet in my daily life I can see that they are normal people like me, random persons, they can be nice or annoying, but it is clear that they are normal people and that I should treat them with a minimum of respect and politeness that I should show to everyone, no matter where they come from. It can happen more easily that we forget these things in the online world. Then the stereotypes and prejudices can soon move in front. It could be that I have never met a Muslim in my life, or that I have never met an Israeli. I see and hear all kind of messages in the media, I see terrorists committing attacks in name of Islam, I read negative articles of what the Israelian government has done in Lebanon. It could happen then that I start to dislike Muslims or Israeli’s in general. There is a very big chance that if I would meet Muslims or Israeli’s in real life, that there would be many of them that I would like or at least not specifically dislike, I would think that they are normal people like from other countries or other religions. But this experience that these groups are normal people, like from any other group, there is a big chance that I will not have that experience on Orkut. There are many Muslims there who say similar things like Islamic terrorists, or at least it might sound like that in the ears of non-Muslims. If I think negatively about them, then I might say negative things about them and then they will start to shout back. And then I can say: “you see, I told you that Muslims are aggressive barbarians”. This while if a Muslim in the street asks me the way to the railway station, I won’t reply by saying that “the Quran is not from God” or that “Muslims cannot understand what the Pope said”. The participants in a youth exchange usually have a much more positive attitude towards “the other” to start with than many Orkuters have. The participants of an exchange like to get to know other cultures, they want to have fun together and to do useful voluntary work together, no matter where everybody comes from or what their culture or belief is like. They like the diversity, learning different languages, tasting different food. If they would think that “the others” are aggressive barbarians then they would not want to take part in a youth exchange with them.

And this is different in the Orkut world. Some Orkuters have as their mission to fight against Islam/Muslims, or Hindu’s, or Israeli’s/Jews, or Palestinians, or Americans, or whoever. If your mission is to fight such a group, to show that an ideology is wrong or that such a group is dangerous, then you are not going to say: “oh how wonderful to meet so many people of this group here, let’s listen with an open mind to what they say and let’s try to decrease my own prejudices and stereotyped way of thinking with regard to this group…”

- The second difference is – as I said – that an intercultural learning process also needs coaching. And there are no coaches / teachers at Orkut. People don’t know which skills are needed for intercultural contact and nobody teaches them how they can improve these skills. So the chances for a peaceful constructive intercultural dialogue at Orkut, especially in communities with sensitive topics with regard to politics, culture and religion, are not so big I think. Still I personally find it very very interesting to read these discussions, to see how people treat “the other” with a totally different cultural / religious / geographical background. Looks like “Levinas’ laboratory” :-)

Still I personally find it very very interesting to read these discussions, to see how people treat “the other” with a totally different cultural / religious / geographical background. Looks like “Levinas’ laboratory” :-)

And sometimes it works to promote peace, sometimes they decide to end their conflicts and to respect each other as equal human beings (although the peace usually doesn't last very long). At such moments I am very happy. I am also happy if I succeeded in explaining the problem of the “dehumanisation of the other” as Levinas calls it. That people say: “I understand what you mean and I am sorry for what I said.” That motivates me to go on with my plea for humanity.

9/12/2006

Kleuters en een geitje

Germany lacks "gezelligheid" according to Dutch youth

To make my post easier to read, I will post the fifth comment of the thread below as a separate post ...

To make my post easier to read, I will post the fifth comment of the thread below as a separate post ...Here is another example of negative irrational immoral images about Germans, this time from Dutch youngsters. Below are some results from a survey called "Burenverdriet" (neighbour sadness) that was carried out by the Clingendael Institute in 1997, among more than 1000 pupils from 13 highschools in the Netherlands.

A similar kind of research had been carried out in 1995 and 1993.

And one more remark before I start: This research is from almost ten years ago. There are also many other researches done with an opposite outcome, which show that the Dutch youth are starting to think more positive about Germany. Berlin is very popular for going out, and for the rest the Dutch youth is not the whole day busy thinking how stupid Germans are (fortunately). I think that the outcome of the Clingendael research will have been influenced by the way the questions were asked. I doubt for instance if the youth have chosen the words militant, dominant and aggressive all by themselves, or if they were mentioned in the question and it was enough for the respondents to say that they agreed.

The reason why I am referring to this research is because these emotions do exist still among youth, and there are not many improvements visible - also if you compare the '93, '95 and '97 surveys. The war happened more than 60 years ago, it is worrying to see that half of the Dutch youth currently still thinks that Germany wants to conquer other countries.

The research report - which is quoted below - is in Dutch. So I will start with a summary in English.

Outcome of the 1997 survey:

- From all the EU member states Germany - and the German population - is considered to be the least sympathetic among Dutch youth.

- The scores of negative emotions towards a people are the strongest against Germans. These negative emotions depend mainly on the views that the youngsters have about Germans (stereotypes and clichés) and the direct contact they have with Germany.

- Dutch youngsters like Germany the least to move to.

- They also like Germany the least as their neighbour.

- It turned out that they don't know much about Germany.

- Almost half of the sample considers Germans to be militant, dominant and arrogant (1993).

- Only one-fifth of the respondents considers Germany to be a peace-loving country (1993).

- Negative messages about Germany and Germans reach the respondents mainly through their grandparents and friends.

- 62% of the respondents call Germany democratic.

- 27% thinks that Germany has got a big difference between rich and poor.

- 42% thinks that Germany doesn't accept many refugees.

- Germans have the lowest score with regard to "gezelligheid" (cosiness), friendliness, and easygoingness of the EU.

Text of the report:

De resultaten van dit onderzoek tonen aan dat de houding van jongeren jegens Duitsland en Duitsers weliswaar positiever geworden is, maar dat deze in essentie onveranderd is gebleven vergeleken met het onderzoek van 1995 [Dekker, Aspeslagh, Du Bois-Reymond, 1997]. Duitsland blijft van alle lidstaten van de Europese Unie het land waar de minste sympathie naar blijkt uit te gaan.

Uit het onderzoek blijken emoties de belangrijkste verklaring voor deze houdingen te vormen: Duitsland scoort het hoogst op negatieve emoties. Deze emoties ten aanzien van Duitsland worden door hun hardnekkigheid gekenmerkt, waarvan de wortels in het verleden liggen. Ze kunnen, bij wijze van spreken, er niet met een pincet uitgehaald worden. Wijziging van zulke, door hecht verankerde emoties bepaalde, negatieve houdingen vergt een aanpak met lange adem.

De eerste empirische studie van het Instituut Clingendael en de Rijksuniversiteit Leiden dateert van 1993. Ruim achttienhonderd jongeren op scholen voor voortgezet onderwijs vulden tijdens een lesuur een vragenlijst in. Een meerderheid van de ondervraagde jongeren had een negatieve attitude tegenover Duitsland. De attitude ten aanzien van de andere EU-landen was veel positiever. Objectieve kennis over Duitsland bleek beperkt aanwezig. Bijna de helft zag Duitsland als oorlogszuchtig en als een land dat de wereld wil overheersen. Eenderde geloofde dat Duitsland weinig vluchtelingen opnam. Slechts twee op de tien ondervraagden zagen Duitsland als een vredelievend land. De meerderheid van de respondenten vond Duitsers overheersend en arrogant. Een aanzienlijk effect op de attitude hadden de opvatting over Duitsland (clichés en stereotypen) en het wel of niet direct contact hebben met Duitsland.

In de tweede studie in 1995 werden opnieuw schoolgaande jongeren geënquêteerd. Ruim duizend jongeren op scholen voor Mavo, Havo, en Vwo, verdeeld over het hele land, deden aan dit nieuwe onderzoek mee. Tijdens een lesuur beantwoordden de respondenten opnieuw een vragenlijst onder toezicht van één van de onderzoekers. Naast vragen over de attitude tegenover Duitsland zijn opnieuw vragen gesteld over clichés van Duitsland, stereotypen van Duitsers en over direct contact. Nieuw in het onderzoek waren vragen naar emoties ten aanzien van Duitsland en vragen naar de attitude tegenover het eigen land. Vergeleken met het eerste onderzoek was de attitude jegens Duitsland in 1995 aanzienlijk minder negatief, evenals de clichés en stereotypen. Duitsland was echter ook bij dit onderzoek de EU-lidstaat met het hoogste percentage negatieve attituden. Het land kreeg wederom de laagste gemiddelde sympathie score. Het kreeg opnieuw de minste voorkeur om naar te verhuizen (tezamen met Ierland). Duitsers had men het liever niet als potentiële buren. Ook in 1995 was Duitsland de EU-lidstaat die op het hoogste percentage negatieve attituden van jonge Nederlanders kon rekenen. De veronderstelling dat de racistische aanslagen in Duitsland een zeer grote invloed op de beeldvorming hadden, was op zich juist. Het verschil was een beweging van een sterk negatief naar een negatief beeld. De meeste invloed op de Duitsland attitude hadden emoties, die Duitsland en Duitsers oproepen, de clichés van Duitsland, en de stereotypen van Duitsers. Negatieve berichten over Duitsers komen, in de perceptie van jongeren, vooral van hun grootouders en vrienden. Duitsland is evenals in 1993 en 1995 ook bij dit derde onderzoek de EU-lidstaat met het hoogste percentage negatieve attituden (38%). Het land kreeg wederom de laagste gemiddelde sympathiescore. Het kreeg opnieuw de minste voorkeur als land om naar te verhuizen. Duitsers kregen opnieuw weinig voorkeur als potentiële buren (tezamen met Ieren, Zweden, Grieken, Portugezen, en Finnen).

Duitsland scoorde ook in 1997 het hoogst op oorlogszuchtig (samen met Frankrijk). Slechts drie clichés zijn behoorlijk veranderd. In 1995 werd Duitsland democratisch genoemd door 72 procent van de scholieren, in 1997 noemt 62 procent dat (-10%). In 1995 geloofde 18 procent van de ondervraagden dat Duitsland grote verschillen tussen arm en rijk kende, twee jaar later gelooft 27 procent dat (+9%). Ook het percentage respondenten dat gelooft dat Duitsland weinig vluchtelingen opneemt is toegenomen (+9%). De stereotypen van Duitsers zijn in 1997 zo goed als dezelfde als in 1995. Opnieuw scoorden Duitsers het hoogst op overheersend zijn en arrogantie en het laagst op gezelligheid, vriendelijkheid, en het gemakkelijk in de omgang zijn. Dat geldt ook voor de emoties die Duitsland oproept. Ook de rapportages van de respondenten over de frequentie van verblijf in Duitsland verschillen nauwelijks. Over het geheel genomen zijn de attituden, beelden, en emoties ten aanzien van Duitsland weinig veranderd. De verbetering die in 1995 is gesignaleerd ten opzichte van 1993 heeft zich niet doorgezet. Dit ondanks de vele activiteiten die sinds 1993 en ook na 1995 zijn ondernomen om de relatie tussen Nederland en Duitsland en de beeldvorming van Duitsland te verbeteren.

"Und du meinst, das hier wird nicht villeicht falsch verstanden...?"

"Ach was! So viel Humor werden selbst die Käseköppe haben!"

9/10/2006

There is nothing special about being German

Below is a text I wrote after reading “Lust for suffering” (Lijdenslust) from the Jewish writer Marcel Möring. He writes about the nonsense of the television priests and therapists who promise instant happiness. He thinks that we should accept suffering as a necessary part of our life and he even thinks that happiness is just an illusion. Although I don’t agree completely with what he says, I find his views interesting. However, in this post I don’t want to write about his ideas about happiness in general but about what he said about the role of Germans with regard to the post-war generations.

Below is a text I wrote after reading “Lust for suffering” (Lijdenslust) from the Jewish writer Marcel Möring. He writes about the nonsense of the television priests and therapists who promise instant happiness. He thinks that we should accept suffering as a necessary part of our life and he even thinks that happiness is just an illusion. Although I don’t agree completely with what he says, I find his views interesting. However, in this post I don’t want to write about his ideas about happiness in general but about what he said about the role of Germans with regard to the post-war generations.Marcel Möring says that he thinks that the generation of Germans who were born after the war should not take the guilt upon them of the horrors and crimes of the war. People are only responsible for their own actions, they should not feel responsible for what the generation before them did. And it is dangerous to allow the younger generation to romanticize the German feeling of guilt and suffering. When these feelings of guilt don’t stop, something new will grow on it, a feeling of bitterness and a feeling of being special as Germans, with the role they played in the history. This while Möring thinks that young Germans shouldn’t feel special at all. They should realise that they did host the inhuman and destructive ideology of fascism, but that it was in fact by accident that this happened in Germany. This terrible beast, the “Nazi beast”, could have been hosted anywhere, just as well in the Netherlands, in the US or among the Eskimo’s. There is nothing intrinsically beastial in the nature of Germans.

While travelling through Germany, Möring met many young Germans with a very old feeling of guilt, a feeling which is becoming more and more “German”. The idea that the offenders / committers of crimes would bare children who are criminals themselves, by definition, is ridiculous. The children and the grandchildren cannot be held accountable for things they didn’t do themselves. The belief that the destiny of future generations would be determined by past generations, that the new generation would carry the dust of the history, comes from the idea that a free will doesn’t exist, that we would completely be determined and imprisoned by our history, as an inevitable chain of events which we cannot change.

I wanted to make a remark here – Möring does not mention this – that this idea can also be found with Heidegger; the idea that the future is fixed, determined by the past. The idea e.g. that Germans are autochthonous because of their being rooted in the German history, something which doesn’t count for Jewish Diaspora. This makes them totally unfree, a people is determined by the history of that people, there is no way that an individual can liberate him or herself from that. Then a people can have a special mission or role, as opposed to other peoples. Their speciality is based on their ethnicity / roots and it is inevitable. No other people can replace that speciality and the related mission.

Möring protests against this idea, there is nothing special about being German and there is no special German role or mission.

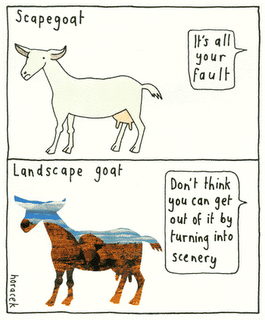

It is good to know the history of your people, including what exactly happened in the Second World War, but Germans should not create an intrinsic inevitable everlasting “German” feeling of guilt. Such a feeling is dangerous, unjustified and incorrect. In fact we don’t have to be afraid when a people feels strong, the most dangerous are feelings of weakness, sufferance and anger about perceived injustice. The embittered suffering in which we don’t consider our pain as a necessary part of our lives, but as something reproachable, is dangerous. When the suffering is abstract and it is impossible to point a clear cause for it, then an everlasting scapegoat with mythical proportions should be appointed. In this way the Jews were appointed as scapegoats before the Second World War. So to prevent a people from being named as scapegoats, these sentiments of drowning in feelings of an endless suffering and frustration should not be accepted. To drawn in such romantic feelings of an endless suffering prepares the ground for a war like the Second World War (at that time in the 30s there was also such a feeling of suffering, frustration and deprivation). The healthy idea that Germany is a normal country with a normal people, like any other, could in the long run be replaced by the unhealthy idea that Germans will for ever be guilty of what they have done in the war, and that through that, they have become victims of their own guilt. This intoxicating perfume of feeling injured and hurt, combined with the feeling of being a special chosen people with a mission, this makes that bitterness and hate can grow very fast.

It is good to know the history of your people, including what exactly happened in the Second World War, but Germans should not create an intrinsic inevitable everlasting “German” feeling of guilt. Such a feeling is dangerous, unjustified and incorrect. In fact we don’t have to be afraid when a people feels strong, the most dangerous are feelings of weakness, sufferance and anger about perceived injustice. The embittered suffering in which we don’t consider our pain as a necessary part of our lives, but as something reproachable, is dangerous. When the suffering is abstract and it is impossible to point a clear cause for it, then an everlasting scapegoat with mythical proportions should be appointed. In this way the Jews were appointed as scapegoats before the Second World War. So to prevent a people from being named as scapegoats, these sentiments of drowning in feelings of an endless suffering and frustration should not be accepted. To drawn in such romantic feelings of an endless suffering prepares the ground for a war like the Second World War (at that time in the 30s there was also such a feeling of suffering, frustration and deprivation). The healthy idea that Germany is a normal country with a normal people, like any other, could in the long run be replaced by the unhealthy idea that Germans will for ever be guilty of what they have done in the war, and that through that, they have become victims of their own guilt. This intoxicating perfume of feeling injured and hurt, combined with the feeling of being a special chosen people with a mission, this makes that bitterness and hate can grow very fast.I think this analysis from Möring is fundamental. Human beings should always consider each other as being completely equal in their humanness, there are no special peoples, not because of their enrootedness, and not because of their role in history neither. We are all equal so it is not possible to consider your own people as special and superior, which could otherwise then be used as a justification to appoint another people as inferior, as scapegoats, which means that their rights can be taken away, they can be discriminated, excluded from society. We are all equal, discrimination based on race, ethnicity, culture or religion can never be justified. Different countries play different roles in history, these roles don’t stick to a people, other countries could have played the same role. There is nothing wrong with being German, there is something very wrong with Hitler because he started the Second World War. It would have been just as wrong if he had been French or English or Jewish Diaspora, for that matter.

In my opinion this is why Heidegger’s philosophy of enrootment is problematic. Germans are determined to be authentic, Jewish Diaspora is determined to be rootless. As a consequence Heidegger refused job applications from Jews at his university. It is this historic determination which makes that different ethnicities are no longer equal and that some peoples can be discriminated, it was this philosophy that Levinas protested against in his commentaries about the philosophy of Hitlerism and Heidegger’s philosophy.

9/04/2006

Peace and International Relations

Below is the code of conduct I have written as a moderator of "International Relations" at Orkut. Maybe you also like to read what I wrote there. It starts with an explanation of the rules of the discussion group, then the procedure to be unbanned, then some philosophy and finally some lyrics about peace from U2 and Paul Simon...

Below is the code of conduct I have written as a moderator of "International Relations" at Orkut. Maybe you also like to read what I wrote there. It starts with an explanation of the rules of the discussion group, then the procedure to be unbanned, then some philosophy and finally some lyrics about peace from U2 and Paul Simon...Ten rules of the International Relations community

- We are NOT a hate community for fights between countries, cultures or religions.

- Take a look at the existing threads to avoid repeated topics.

- No preaching is allowed. It is possible to write about religion but it should be relevant to international relations then. It could be for instance that when somebody else has presented a wrong image of a religion at IR, you start a thread to take away misconceptions. But general threads with information about a certain religion or holy book should be posted in communities about religious topics. Preaching from atheists is not allowed either. (Meaning of “to preach” according to Cambridge Dictionaries Online: “to try to persuade other people to believe in a particular belief or follow a particular way of life”.) Threads of harm are not allowed either.

- Personal insults to Orkuters (and their family / friends) are not allowed in IR. So threads to “expose” how stupid somebody is, are not allowed either. It is much better to just talk about topics related to politics and international relations. If you are angry with an Orkuter, have your fight in scrapbooks then or anywhere, but not in IR. So regular bad words like moron, troll, asshole are not allowed. Calling people e.g. kafir or Paki is not allowed either. It was considered to be ok to use the word “Commie”, though. The moderator of IR cannot be held accountable for what people say in other communities or in scrapbooks. You should not quote or complain about these things in IR. In the scrapbook of the moderator the rules of IR don’t apply, so if you want to complain about behaviour of IR members in a not so polite way that can be done in the scrapbook of the moderator (although there are limits to the amount of shit that can be posted there as well). What people write in scrapbooks can never be a reason to ban them from IR.

- Serious insults to a certain culture, people or religion are not allowed. To say that Pakistani don’t have human feelings like shame, or that American soldiers are babykillers, these are serious insults towards a certain group of people (country / culture / religion / profession), so they are not allowed in IR. Don’t say that someone is a “typical Indian”, don’t talk about “people like you”. We are all unique individuals, to make generalisations about everybody else with the same religion / culture etc. is not necessary and not correct. And don’t abuse any prophets, gods, holy books, etc.

It is ok to criticize certain aspects of a religion or e.g. decisions from a government. But do try to make your criticism specific then, don’t include the whole world and all times in it. Try to post your criticism in such a way that it is with respect for other people’s faith and culture. Islam bashing, Hinduism bashing, mudslinging parties, endless fights, hate spreading, these things are not allowed. Behave a bit responsible and mature please, don’t try to hide away an “X bashing” thread by presenting it as neutral criticism. X-haters had better go somewhere else, instead of seeing it as their mission to fight X (a certain culture or religion) in IR. Extremely offensive profile pictures and descriptions are not allowed. Profiles which are making jokes about other Orkuters will not get access to IR. Serious insults to a religion or promotion of extremism / racism are not be allowed. In the past I refused access to “Prophet Swine”, “Om & Bhaskar” and Nazrallah with breasts. - Please don't use this community to make publicity for your website, certainly not if it's not related to International Relations. These threads will be deleted.

- Only write in English here please, so we can all understand it (or provide the translation if you post in another language). And try to write in proper English, so no SMS / MSN language, don’t write in caps lock / bold only / all colours mixed. This will not be a reason to ban IR members, but it is just annoying for others if they have to do extra efforts to read what you wrote, which also makes the chance bigger that nobody will really read what you write.

- Repeated attempts to hijack a thread are not allowed (certainly when the new topic is not relevant for IR or not funny).

- If anyone who joins IR threatens to or incite others to report this community and/or its members as bogus, he/she will be banned.

What will happen when I (repeatedly) violate the rules? The moderator will give you a warning to stop the violations. If you refuse to take back your words and/or you continue to violate the rules, the moderator will ban you. You can never come back the same day. But if you send the moderator a scrap that you will respect the rules from now on, you will be unbanned and your request to rejoin IR will be accepted the next day.

The moderator will give you a warning to stop the violations. If you refuse to take back your words and/or you continue to violate the rules, the moderator will ban you. You can never come back the same day. But if you send the moderator a scrap that you will respect the rules from now on, you will be unbanned and your request to rejoin IR will be accepted the next day.

Some philosophy

Why are we here at Orkut talking with each other? Are we here only to say that Pakistani are barbarians and that Hindu’s have such weird gods and that Bush is a fascist and that the Dutch have a suicidal attitude of extreme political correctness? Are we here to have useless endless fights with each other, insulting and hurting each other about things which we find most important in life? Do we have as a mission to prove that “the other” is wrong and bad and dangerous? Do we want that the violence and aggression towards innocent people, the endless wars of the offline world, do we want to copy and continue these wars into the online world? Or do we want to make a difference, do we want to strive for peace together, while realising that we are all equal as human beings, with respect for each other? It is not easy to have discussions here with totally different people. There is a lot of anger against injustice, frustration, hate, both in the offline and the online world.

Or do we want to make a difference, do we want to strive for peace together, while realising that we are all equal as human beings, with respect for each other? It is not easy to have discussions here with totally different people. There is a lot of anger against injustice, frustration, hate, both in the offline and the online world.

Orkuters want to be able to speak out for themselves, of course. They want to fight against injustice by saying what they think. Even if this is sometimes offensive for others, they think that “the truth should be told”. But what they consider to be an absolute truth is totally untrue in the eyes of others. I do find freedom of expression important, even if it hurts others. I think that nobody possesses the absolute truth. For sure my own views are coloured by my perspective as a lunatic liberal. Who am I, as a moderator, to determine which views are allowed to be expressed in IR and which not?

An IR member once said it very well: it is not about which views are being expressed, it is about how this is being done. It is very well possible to explain that it is not your intention to insult peaceful normal people who quietly follow their personal belief. You can always start a thread by saying something like that. And then you can protest against women being stoned to death, abortions, environment pollution, innocent people being killed, governments who take away universal human rights from certain groups, etc.

An IR member once said it very well: it is not about which views are being expressed, it is about how this is being done. It is very well possible to explain that it is not your intention to insult peaceful normal people who quietly follow their personal belief. You can always start a thread by saying something like that. And then you can protest against women being stoned to death, abortions, environment pollution, innocent people being killed, governments who take away universal human rights from certain groups, etc.

Be precise with your criticism, don’t disapprove of a whole religion or culture, describe precise practices which are carried out in the name of it, and explain exactly why you disapprove of these practices. The chance is much bigger then that your post will lead to an interesting constructive dialogue than when you start to shout at a certain religion. The chance will be very big that in reaction people will start to shout back and this bashing party thread becomes totally useless then…

Songs about peace

Lay down

Lay down your guns

All your daughters of Zion

All your Abraham sons

Baby don't fight

We can talk this thing through

Heaven on earth

We need it now

I’m sick of all of this

Hanging around

Sick of sorrow

I’m sick of the pain

And it’s already gone too far

You said that if you go in hard

You won't get hurt

Jesus can you take the time

To throw a drowning man a line

Tell the ones who hear no sound

Whose sons are living in the ground

Peace on earth

No one cries like a mother cries

For peace on earth

She never got to say goodbye

To see the colour in his eyes

Now he’s in the dirt

Peace on earth

You say love is a temple

You ask me to enter

But then you make me crawl

And I can't be holding on

To what you got

When all you've got is hurt

One love, one blood, one life

You got to do what you should

One life with each other

Sisters, brothers

But we're not the same

We got to carry each other

And I believe in the future

We shall suffer no more

Maybe not in my lifetime

But in yours I feel sure

Who says “hard times”?

I'm used to them

And sometimes even music

Cannot substitute for tears

9/02/2006

Is the Quran from God?

After having talked to "Simon", I kept thinking about why I find it a bad thing to start an Orkut community (discussion group) with the title: "Quran is not from God".

After having talked to "Simon", I kept thinking about why I find it a bad thing to start an Orkut community (discussion group) with the title: "Quran is not from God".I decided to ask the community why they want to have it. The answer was something like "why not". Freedom of expression means that people should be allowed to say that kind of things.

This argument is used very often, also e.g. with the Danish cartoons. A possible reply is that freedom of expression is not the same as the right to unnecessary insults. Why do atheists want to talk about the holy book and the God of Muslims, just leave that up to them. Then somebody said the atheists are just discussing it among themselves. I replied that it is not among themselves in this online world in which there are also many Muslims.

After a long discussion and some sleep I decided to start a new thread to explain my own concept of God.

This is what I wrote:

"Why am I posting in this community?

Why do I find it important to let my voice be heard as a protest against the claim that the Quran is not from God?

Maybe some people will understand what I mean if I describe the way I believe myself.

What matters most in a belief, is it what the priests / imams say? Is it what is written in the holy books? Is the most important thing that I obey to everything that the church / mosque asks from me? Am I a bad person if I skip praying or going to the church once?Should everything what is written in the holy books be for the full 100% literally true?

I don't believe in that way. As a child I could feel the presence of God. For me God has always been a God of Goodness and Love. The one who listens with care and great attention, the one who understands everything, who forgives, who gives me the strength to hold on. It's a friendly God to whom you can always go, also if nobody else has time for you. He gives the feeling that everything will be alright, the times can be very very difficult, lonely, sad. But he still supports me, he is always with me, he will never leave me and say: forget about me, from now on you will be alone. He promises me that at the end of the desert it will be beautiful and good. He sets me free and gives me the power to fight for goodness. I believe that there is one God, an almighty God of Infinity. Jews, Christians and Muslims and also people with other beliefs, they all believe in this same God. God doesn't talk to us directly. We can feel some of his presence but he doesn't appear on television or internet to tell the whole world once more what he wants for our humanity. So how do we know what he is like and what he wants for us? The only thing we have are the holy books. The prophets have died a long time ago. The priests and imams and rabbi's are human beings. It is possible that they spread the message of God but it is also possible that they just spread their own message.

So we have 3 religious books. These books were written by human beings. It was not that God was sitting on a cloud with a pencil, writing everything and then throwing it down to earth. The writers have heard the word of God, I think. There are many similarities between the 3 books. In all 3 bookd a story is told of how a good God tells his believers to be good human beings. The 3 books are each of them a guide to tell people how they should live. I find the lessons to turn the other cheek, to help your neighbour and the stranger, to be tolerant, to strive together for peace and justice as brothers and sisters, to be good to each other and to God, these lessons I find the most important. Maybe not everything which is written in the Quran is relevant, literally, for us right now. Maybe the writers at that time have included in the book some rules which applied for that time but not now anymore. And there are also some rules which say that we should only listen to the real God, not to fake human gods, we should not loose our way and move away from goodness. For people who don't want to listen to such an abstract message, they maybe understand it better when rewards are promised when they do it good and punishments when they are bad. No need to worry too much about the "worst creatures" if you try your best to be a good person yourself.So I am convinced that the Quran is from God, even if the people who wrote it down maybe didn't do that completely correct always. I also think that what the 3 books have in common has got the biggest chance of being exactly the way God meant it.Let's turn it around now, let's assume that the Quran is not from God, it has got nothing to do with God. And the Bible and the Torah neither. God doesn't talk to us on television.How can we know anything at all about God, then? We can decide to move to Hinduism or Budhism or animism. But if I want to remain a Christian, and I throw away the Bible, how do I know anything about God then? That's impossible.

God could be the devil. He good be a green Marsian with 8 arms. It doesn't make sense to believe if you don't know in what you should believe. So I think it is impossible to be a Christian without the Bible, impossible to be a Muslim without the Quran and impossible to be a Jew without the Torah. And if you do study these books, they can certainly help you in life. They are strong as ethical guides, practical, poetical. It is good to read the stories and to learn from it. I think these books are meant to be the word of God, the good God that I believe in. So I want to read them in that way."

It is difficult to have this kind of discussions with atheists / Islam-haters. They look at what terrorists think and do. They look at the book which inspired them for that. And then they draw their conclusions. By that way denying that over a billion moderate peaceful Muslims read the holy book of their faith in a completely different way.

After my text they wanted to prove that an omniscient and omnipotent God cannot exist. My God became defined as an unrealistic "cream cheese and coconut God". Then I explained that this is not a God I invented but the God from Levinas, Buber and Rosenzweig. So far they haven't been able to prove that this God doesn't exist, cannot exist.

This community is also a case of the systematic denial of the other. A refusal to reflect with an open mind. A refusal to try to step for one moment out of your own atheist shoes and to step into the shoes of a moderate Muslim. For Levinas the starting point is God. God as infinity, of whom we can see a glimpse through our relation with the other. The starting point is that God is good and that God exists. Then there are religions and religious leaders and religious books and believers. These books can help us to understand God. Of course the holy books from the Abrahamic religions are coming from the Abrahamic God.

Atheists can ask questions, always, about everything. How do we know that God exists? How do we know that the holy books are from him? Why are there three of them, not one? If God has got so much power, why doesn't he stop the suffering and injustice in the world? If God knows that bad things are going to happen, why doesn't he change the future? And if he does, why are so many bad things happening then?

Respectful questions and discussions between people who consider each other as equal and who acept from each other that they have opposing views.

Then I think that the community title should be a question: Is the Quran from God?

Then everybody can give their personal answers and they can exchange views on a basis of equality.

Simon's reaction is funny:

"NO WAY!!!We KNOW the Quran is not from god. There isn't any need for a question mark. We AFFIRM the fact that it is a mere book. That's the whole point. "

He also said:

"You know that I don't think much of anyone who takes that book completely seriously. It's a completely moronic. If any person is offended by our community title, it's his or her problem, not ours."

There you go. Simon knows the absolute truth, the Quran is a moronic book, he doesn't think much about the over an billion people who take the book seriously. He can insult them as much as he likes, that is their problem...