4/28/2006

Religion, dogmatism and oppression

Orkuter 1 says:

Rights are not given by religion. We are born with our rights.Funny enough, it is religion that removes your rights. With what authority I don't know. Fools are the ones who believe in religious leaders who claim to be the authority of any religion in the world.

Orkuter 2 says:

Orkuter 2 says:Not only that, religion will tell u:

1. whether sun moves around earth or earth moves around sun.

2. evolution theory is right or wrong.

3. killing infidels right or not.

4. what u think right or not.

5. how many u should marry.

6. some says dont question what is written in so called holy books, just believe and act accordingly.

7. some goes to the highest extent and say how to walk, how to take bath, how to sleep, how to have sex, what to say in different situations,...

in a word a FULL CODE OF LIFE. (u just born, read and thats all. there is no use of ur own intelligence!!!, u r FREE of thinking....................)

I replied:

Other versions of religion exist as well fortunately.

I have read many books from Emmanuel Levinas (Jewish philosopher) lately. He emphasizes the own responsibility of humans all the time. Ethics form the basis of all human relations according to Levinas. And ethics is what matters in the first place, that we are good to each other as human beings. For Levinas God is in a way secondary (and formal religion tertiary). If we are good to each other we can see a glimpse of God through the Other, the person that I am good to. Levinas is always a bit suspicious towards religious leaders. Maybe they are looking for power on earth and misusing religion for that. The basis for ethics and religion lies at the personal level. The other person wakes up my conscience when I see his or her face. That is the best level for ethical responsibility. A more macro-level has a bigger chance of evolving into a totalitarian system which is immoral.

4/25/2006

Intercultural dialogues

Below is a text I wrote for the Orkut community "International Relations", as a moderator of that community. The reason why I am publishing it here at my blog is that this topic is of course very relevant in relation to the topic of my dissertation: to apply the philosophy of Levinas to intercultural contact.

Below is a text I wrote for the Orkut community "International Relations", as a moderator of that community. The reason why I am publishing it here at my blog is that this topic is of course very relevant in relation to the topic of my dissertation: to apply the philosophy of Levinas to intercultural contact.When I had just started as a moderator, Tanzeel asked me to write an introduction message to the community. I have been thinking long time about what I should say then. Now I decided to write about the art of intercultural dialogues. I am reading the book “My place is no place, meetings between worldviews” (http://www.ktu.nl/berichten/boek/181 , but it’s in Dutch). The book contains an essay about intercultural dialogues.

This is what we are doing all the time in International Relations: we are having intercultural dialogues.

In the book the writer (Heinz Kimmerle) mentions 4 necessary conditions to have a real intercultural dialogue:

- The debating partners should treat each other completely on a basis of equality.

- There are both similarities and differences in their points of view (because if there are no differences it is not intercultural but monocultural and if there are totally no similarities, no overlap, it will be very hard to understand each other).

- The debating partners are open-minded, they are open for the idea that their own views might be wrong or should be changed.

- The debating partners think that they others have something interesting to say to them, that they can learn from each other, that the others say things to them which they could never have thought of all by themselves.

The recognition of equality is very important, and the open-mindedness as well. If these two are absent, the chance is very big that endless figths will arise in which each party tries to prove to be right, doesn’t listen to what the other says, and keeps repeating their own arguments, with more and more aggressiveness because the debate is going nowhere.

The recognition of equality is very important, and the open-mindedness as well. If these two are absent, the chance is very big that endless figths will arise in which each party tries to prove to be right, doesn’t listen to what the other says, and keeps repeating their own arguments, with more and more aggressiveness because the debate is going nowhere.Kimmerle argues that the aim of an intercultural dialogue is not necessarily to reach an agreement between the different partners. Different cultures can be compared with each other, people from different cultures can talk with each other and understand each other. But at the same time the differences between cultures can be “radical” in the literal sense of the word (radix means roots in Latin, so it means fundamental). The aim of an intercultural dialogue is not that differences disappear completely. The aim is that the participants widen their horizon by listening to other points of view. The dialogues can lead to other positions than the original positions from each of the debating partners. A real intercultural dialogue is based on patience, attention, empathy, respect and open-mindedness towards the other, that leads to a constructive dialogue. You try to put your own views, judgements and prejudices aside for a while and to really listen to what the other says. Then you explain precisely how you look at the world yourself, and that you start to exchange views about that, backed up with resources and good arguments.

Maybe we could try a bit more, all together, to have real intercultural dialogues here instead of “mud slinging and bashing parties”? ;-)

4/18/2006

Hoe kunnen we democratisering en verbetering van mensenrechten stimuleren?

Welke antwoorden we voor bepaalde problemen bedenken hangt gedeeltelijk af van hoe we de vraag stellen. Wesley van de Berg zegt in een Volkskrant artikel van 15 april j.l. dat het WRR rapport “Dynamiek in islamitisch activisme” niet de vraag stelt waar het om gaat. Volgens Van de Berg is de vraag die zij stellen: “Zijn er tekenen van hervorming in de moslimwereld?”, terwijl de vraag volgens hem zou moeten zijn: “Kan de moslimgemeenschap in Nederland - en West-Europa - op termijn de democratische rechtsstaat dragen?”

De vragen die in het rapport zelf genoemd staan zijn:

- Welke inzichten zijn te ontlenen aan de ontwikkeling sinds de jaren zeventig van islamitisch activisme in relatie tot democratisering en verbetering van mensenrechten?

- Welke aanknopingspunten biedt islamitisch activisme voor toenadering tot concepten van democratie en mensenrechten?

- Welk beleidsperspectief voor Nederland en Europa kan op de langere termijn spanningen rondom vraagstukken van islamitisch activisme binnen de moslimwereld verminderen en processen van democratisering en verbetering van mensenrechten ondersteunen?

De eindconclusie van het rapport luidt:

De eindconclusie van het rapport luidt:“Een klimaat van confrontatie en sjabloondenken schept geen bestendige voorwaarden voor veiligheid, democratisering en toenemend respect voor mensenrechten. Het enig wenselijke alternatief is in te spelen op aanknopingspunten voor democratie en mensenrechten in het islamitisch activisme zelf. De in dit rapport gepresenteerde analyses laten zien dat die aanknopingspunten er wel degelijk zijn.”

De reden om naar aanknopingspunten te zoeken is dus om een negatief klimaat van haat en geweld tegen te gaan die voortkomen uit een vorm van vijandsdenken. Dat vijandsdenken is niet nodig, uit het WRR onderzoek blijkt dat er genoeg aanknopingspunten zijn binnen Islamitisch activisme om democratisering te stimuleren met behulp van insluiting in plaats van uitsluiting van moslims.

Wesley van de Berg betwijfelt of de hervormingen in de moslimwereld (in Nederland) snel genoeg gaan. Van de Berg is van mening dat moslims in Nederland, die in overgrote meerderheid Soennitisch zijn, een historische trend zullen volgen waarin schriftgeleerden met hun koranuitleg een dominante wetbepalende rol zullen spelen. Ten tweede verwacht hij dat de soennitische moslims door de schriftgeleerden te volgen, wetenschappelijke ontwikkeling zullen laten stagneren – “een ontwikkeling die welvaart, welzijn en de democratische rechtsstaat in het westen bevorderde”.

Waarop zijn deze verwachtingen van Van de Berg gebaseerd, voor de Nederlandse samenleving? Zijn er al duidelijke tekenen te zien die in die richting gaan? Ik zie eigenlijk geen van deze tekenen. De kans dat er een dominante wetbepalende rol komt voor invoering van een Islamitische wetgeving in Nederland (in plaats van Nederlandse wetgeving) is heel klein. Moslims vormen een minderheid in Nederland en dat zal nog heel lang zo blijven. De gevestigde orde van Nederlanders zal nooit accepteren dat zij aan de kant worden gezet. En dat Soennitische moslims in Nederland wetenschappelijke ontwikkeling zouden tegenhouden lijkt me ook zeer onwaarschijnlijk. Het lijkt erop dat Van de Berg de Soenitische leer als intrinsiek strijdig ziet met het respecteren van de democratische rechtsstaat.

In zijn artikel “Kunnen Arabieren, democratie en islam door één deur?” bestrijdt Maurits Berger deze stelling. Hij betoogt dat de Islam zich niet slecht verhoudt tot het begrip democratie. Er zijn een aantal andere redenen te noemen waarom het in veel Arabische staten met de democratie vaak niet zo goed gesteld is – Berger noemt als redenen: gebrek aan modernisering, het zijn veelal renteniersstaten, cliëntelisme (patronage), en repressie (door het politie-apparaat). Het gebrek aan democratie zou dan eerder liggen aan de regeringen van de Arabische staten dan aan intrinsieke kenmerken van het islamitische gedachtengoed. Dit blijkt wanneer we het democratische gehalte in Arabische staten vergelijken met het gehalte in andere islamitische landen, zoals Berger zegt: “De aanduiding ‘electorale democratie’ was in 2002 niet van toepassing op enig Arabisch land, maar wel op 14 moslimlanden, waaronder Indonesië, Bangladesh en Turkije (respectievelijk de nummers één, twee en vijf op de lijst van grootste moslimlanden).”

Berger zegt in hetzelfde artikel: “De islam kan dus niet zonder meer aangeduid worden als oorzaak van het gebrek aan democratie in een land. Sterker nog, steeds vaker wordt betoogd dat islam en democratie juist heel goed kunnen samengaan. Dit blijkt uit publikaties van westerse wetenschapslieden en vooral van islamitische vakgenoten, en sinds kort wordt dit ook door politici onderschreven. Onder de westerse wetenschapslieden – die vooral een politiek-sociologische benadering hanteren – zijn er die vaststellen dat de wens tot democratie juist een belangrijk element is in de politiek- islamitische bewegingen. De roep om vrijheid en participatie aan bestuur, maar ook de eisen aan regeringen als accountability en transparency, zijn kenmerkend voor veel

moslimbewegingen.”

Maar Van de Berg gelooft daar zoals gezegd niet in. Hij zegt: “De politiek moet integratie van moslims bevorderen door een politiek van verzoening te voeren, stelt de WRR. Verzoening waarmee? Een beetje aanpappen en hopen op een goede afloop?”

Nee, zeker niet aanpappen en alleen maar hopen dat het goed komt. Bewust handelen is wat nodig is, acties die gericht zijn op verzoening met welwillenden en tegen polarisatie tussen haatdragenden.

Het WRR-rapport formuleert de stimulering van deze vorm van bewust handelen als:

“Een beleid van constructieve betrokkenheid met de moslimwereld dient zich rekenschap te geven van de diversiteit en dynamiek van het islamitisch activisme. Dan kan ook worden onderkend dat de islam in politiek en juridisch opzicht potentieel wel degelijk een belangrijke rol kan spelen in de ontwikkeling van moslimlanden. Het aansluiten bij endogene ontwikkelingen die democratie en mensenrechten bevorderen, kan op de langere termijn tot duurzamer resultaten leiden dan pogingen deze van buitenaf op te leggen. Deze benadering vergt echter wel een cultuuromslag, in de zin dat wordt erkend dat de islam een belangrijk voertuig kan zijn voor het realiseren van democratie en mensenrechten.”

4/10/2006

Confrontatie en verzoening

Het artikel “Confrontatie, geen verzoening” van Ayaan Hirsi Ali, dat afgelopen zaterdag in de Volkskrant stond, maakte mij kwaad toen ik het las. In het artikel reageert zij op het manifest “Eén land, één bevolking” van Anja Meulenbelt, Mohammed Rabbae e.a.. Dat Hirsi Ali zich verzet tegen de onderdrukking en de bedreiging die uitgaat van de radicale islam, dat is goed. Maar daarbij scheert zij de radicale islam over één kam met de islam als geheel, en zij past haar visie toe op het Nederlandse integratievraagstuk in het algemeen, en daarmee richt haar gedachtegoed veel schade aan m.b.t. de kansen in Nederland voor de verschillende bevolkingsgroepen om vreedzaam samen te leven. Woede en angst voor een radicale totalitaire en gewelddadige variant van de Islam maakt soms dat mensen irrationeel gaan denken, dat ze niet meer open en neutraal naar de wereld kijken maar dat zij zich laten verblinden door hun angst en woede. Dat is volgens mij wat er met Ayaan Hirsi Ali gebeurt en wat ook duidelijk blijkt uit de manier waarop zij dat artikel heeft geschreven. Woede en angst leidt tot overdrijving, het geweld en totalitaire denken dat alleen onderdeel uitmaakt van de radicale islam, wordt geprojecteerd op de Islam als geheel.

Het artikel “Confrontatie, geen verzoening” van Ayaan Hirsi Ali, dat afgelopen zaterdag in de Volkskrant stond, maakte mij kwaad toen ik het las. In het artikel reageert zij op het manifest “Eén land, één bevolking” van Anja Meulenbelt, Mohammed Rabbae e.a.. Dat Hirsi Ali zich verzet tegen de onderdrukking en de bedreiging die uitgaat van de radicale islam, dat is goed. Maar daarbij scheert zij de radicale islam over één kam met de islam als geheel, en zij past haar visie toe op het Nederlandse integratievraagstuk in het algemeen, en daarmee richt haar gedachtegoed veel schade aan m.b.t. de kansen in Nederland voor de verschillende bevolkingsgroepen om vreedzaam samen te leven. Woede en angst voor een radicale totalitaire en gewelddadige variant van de Islam maakt soms dat mensen irrationeel gaan denken, dat ze niet meer open en neutraal naar de wereld kijken maar dat zij zich laten verblinden door hun angst en woede. Dat is volgens mij wat er met Ayaan Hirsi Ali gebeurt en wat ook duidelijk blijkt uit de manier waarop zij dat artikel heeft geschreven. Woede en angst leidt tot overdrijving, het geweld en totalitaire denken dat alleen onderdeel uitmaakt van de radicale islam, wordt geprojecteerd op de Islam als geheel.Hirsi Ali schrijft:

“Het grootse verschil van mening tussen de beide denkrichtingen ligt in de opvatting over wat een mensenleven waard is. Westerlingen zien een leven als een heilig doel op zich, een op individuele autonomie gestoelde vrijheid waar je niet mag aankomen.”

Dit is een generalisatie, er kan onmogelijk van alle westerlingen gezegd worden dat zij een mensenleven als een heilig doel op zich zien, anders zou er geen doodstraf zijn in de VS en zouden er niet zoveel moorden worden gepleegd.

“Binnen de islam is alleen de gelovige, de moslim, een mens en zelfs diens leven is alleen heilig als de persoon in kwestie zich aan alle regels heeft gehouden. Het leven van afvalligen is wel heel onheilig, zij mogen, nee moeten zelfs worden gedood.”

Ook dit is een generalisatie / overdrijving. Moslims die vinden dat afvalligen gedood mogen / moeten worden, zijn een kleine minderheid in de wereld. Hier heeft Hirsi Ali het niet over de radicale islam maar over de islam in het algemeen.

“Het westen wordt bedreigd door een zeer gevaarlijke, internationale ideologie die zijn wortels heeft in de radicale islam.”

Uit deze zin blijkt duidelijk een angst voor de radicale islam. En die angst leidt tot overdrijving, het leidt ertoe dat de feiten uit het oog verloren worden en problemen worden opgeblazen tot ongekende grootte. De kern van het probleem is dat Ayaan Hirshi Ali geen onderscheid maakt tussen verschillende kanten van de islam, tussen enerzijds de radicale islam en anderzijds de oorspronkelijke leer van de islam zoals die in de koran is verwoord, en de manier waarop moslims geloven overal over de wereld, waar nogal grote verschillen tussen bestaan.

“Intussen worden overal waar moslims hun geloof serieus nemen de westerse vrijheden bedreigd.”

Wat een grote overdrijving! Op wat voor manier worden westerse vrijheden altijd en overal bedreigd waar mensen hun geloof serieus nemen? Wanneer mensen vijf keer per dag bidden is dat een teken dat zij hun geloof serieus nemen. Op wat voor manier wordt het westen daardoor bedreigd?

“De totalitaire islam bereidt zijn volgelingen voor op een jihad, een heilige oorlog. Demografisch gezien is het nog maar een kwestie van tijd tot de volgelingen van het enige ware geloof ook hier de overhand krijgen.”

Eerst gaat het over de “totalitaire islam”, dan gaat het over “de volgelingen van de islam”, dus in het algemeen, dus ze haalt die twee weer door elkaar.

“Het aantal moslims ligt volgens sussende officiële schattingen op 15 miljoen, maar dat aantal wordt allang betwist door critici van wie sommigen zeggen dat het inmiddels om 40 miljoen gaat.”

Waarom heeft Hirsi Ali het over “sussende schattingen”? Waarom zou het een geruststellende gedachte zijn dat er weinig moslims zijn in Europa? Het gaat hier om alle moslims, niet om alleen extremisten, de meerderheid die gematigd is en gewone burgers in Europa zijn die een geloof aanhangen, daarvan is het toch helemaal niet erg als er meer van zijn dan 15 miljoen?

En hoeveel is dat nu eigenlijk, 15 miljoen of 40 miljoen, in verhouding tot de totale Europese bevolking? De totale bevolking is ruim 700 miljoen, 40 miljoen is daarvan een percentage van 5,7 procent (en dat is dan dus de “niet-sussende” en misschien ook niet kloppende schatting). En dat zijn alle moslims, waarvan de extremistische / totalitaire slechts een heel klein percentage vormen (ongeveer 150 echt gevaarlijke extremisten in Nederland, misschien is hun aantal inmiddels iets toegenomen, maar het blijft een hele kleine minderheid).

Demografisch is het volgens Hirsi Ali een kwestie van tijd tot de totalitaire moslims in Europa de overhand hebben gekregen. Dat kan best slechts een kwestie van tijd zijn, maar dan wel van een ongelooflijk lange tijd, ze moet heel wat eeuwen geduld hebben voordat radicale moslims in Europa de meerderheid van de bevolking zullen vormen. Toch voorziet zij deze situatie zelf al in 2030.

“Als dit scenario tot uitvoering komt, heeft dat grote gevolgen voor joden, homo’s, vrouwen, afvalligen en atheïsten. Christenen zullen dan moeten leven als dhimmi’s, een stille minderheid die extra belasting betaalt en uitgesloten is van bepaalde beroepen.”

Hirsi Ali ziet het al helemaal voor zich. Dit is een vorm van doemdenken die heel ver gaat.. Haar denken gaat uit van een groot aantal aannames die niet kloppen. Ten eerste dus dat het moslim aandeel van de Europese bevolking zo snel zal groeien, ten tweede dat de meerderheid van gematigde moslims zich direct zal aansluiten bij de minderheid van extremisten, ten derde dat de huidige Europese machthebbers zich direct massaal gewonnen zullen geven onder het mom van democratie en ten vierde dat als Europa Islamitisch zou worden het meteen de allerergste variant zou worden die op dit moment in de wereld te vinden is.

“In de reactie op de radicale islam tekenen zich in de politiek, maar ook onder journalisten, publicisten, wetenschappers en burgers twee benaderingen af: de verzoeningsgerichte (zie bijvoorbeeld het pamflet van Mohammed Rabbae en anderen op Forum, 4 april) en de confrontatiezoekende.”

“In de reactie op de radicale islam tekenen zich in de politiek, maar ook onder journalisten, publicisten, wetenschappers en burgers twee benaderingen af: de verzoeningsgerichte (zie bijvoorbeeld het pamflet van Mohammed Rabbae en anderen op Forum, 4 april) en de confrontatiezoekende.”Wacht even, wat zegt Hirsi Ali hier? Ze zegt dat de verzoenende benadering een reactie is op de opkomst van de radicale islam. Dus dat radicale moslims dreigen met geweld en dat de verzoeners zeggen: "laten we vrede met jullie sluiten" (Hirsi Ali spreekt letterlijk van een duivels verbond tussen de verzoeners en de radicale islam). Maar is dat wel de bedoeling van de verzoeners, om vrede te sluiten met gewelddadige extremisten? Nee, de schrijvers van het pamflet hebben het over een heel ander onderwerp, zij hebben het over groeiende tegenstellingen in de Nederlandse samenleving tussen autochtonen en allochtonen. Dat is iets anders dan tussen enkele islamitische extremisten en de rest van Nederland. Vervolgens maakt Hirsi Ali een fijne vergelijking tussen de “verzoeners” en de overlopers naar de nazi’s in de tweede wereldoorlog (beschouwt zij deze politici werkelijk als overlopers naar een fascistische ideologie?). Over de meelopers in de tweede wereldoorlog zegt Hirsi Ali: “door steeds meer toe te geven dachten zij Hitler en Mussolini tevreden te stellen”. Wat een walgelijke vergelijking, alsof Anja Meulenbelt en Mohammed Rabbae willen toegeven aan Mohammed B om hem tevreden te stellen. De vergelijking loopt op alle fronten spaak, de situatie is totaal niet vergelijkbaar (Mohammed B is ook al niet vergelijkbaar met Hitler, niet qua bedreiging die hij voor de wereld vormt).

Een belangrijk verschil tussen de islam en nazisme is dat nazisme als geheel een verdorven ideologie is die van het begin af aan gericht was op onmenselijke racistische uitroeiing. De Islam is een wereldreligie, net als christendom en jodendom, die gericht is op het uitdragen van een geloof. Normaal gesproken, in het overgrote deel van de wereld, gebeurt er niets anders dan dat moslims gewoon hun persoonlijke geloof belijden. Daar is niets mis mee. De islam is een appel die een rotte plek heeft: de radicale islam. Nazisme is een appel die in zijn geheel verrot is. Wat doe je met een rotte plek in een appel? Die probeer je eruit te snijden, zodat de rest van de appel weer goed is. Verzoenen doe je met de rest van de appel, niet met de rotte plek. Als de hele appel rot is dan moet je daar in zijn geheel van af zien te komen. Met de islam is dat niet het geval. En de verzoeners hebben het dus niet speciaal over de islam, zij hebben het net zo goed over niet-moslims. De tegenstellingen worden groter in Nederland, de angst en haat neemt toe. Dat is slecht voor ons land, op die manier kunnen we niet constructief met elkaar samenleven. Hirsi Ali pleit voor confrontatie, geen verzoening. Confrontatie met de radicale islam is prima, laten we er alles aan doen om extremisme en terrorisme tegen te gaan. Maar met de niet-radicale moslims en de allochtonen die geen moslim zijn, daarmee is verzoening heel hard nodig. Hirsi Ali’s simplistische haatzaaierij richt veel te veel schade aan.

En aan het einde maakt ze ook nog even een onsmakelijke grap: “Churchill noemde verzoeners ‘schapen in schaapskleren’ en iedereen weet wat islamieten met schapen doen.” Hier blijkt de haat uit, als ze zich niet had laten verblinden door haar gefrustreerde emoties dan had ze een neutrale feitelijke tekst geschreven met respect voor normale islamieten, dan zou ze dit soort gore grappen niet maken.

4/06/2006

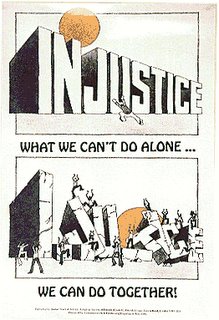

Work of justice

I keep thinking about one of the first topics that I wrote about in this blog: “You have to ask the sheep who is the wolf”. The last months I noticed that my passion to strive for justice is growing. My doubts are decreasing about if I can actually objectively know if my feeling that a certain situation is unfair, if that is true in reality or not. In fact I started to care less about simple objectivity.

I keep thinking about one of the first topics that I wrote about in this blog: “You have to ask the sheep who is the wolf”. The last months I noticed that my passion to strive for justice is growing. My doubts are decreasing about if I can actually objectively know if my feeling that a certain situation is unfair, if that is true in reality or not. In fact I started to care less about simple objectivity.This Saturday I will participate in a conference about Levinas in Utrecht (lecturer: dr. Marcel Poorthuis). In the introduction note the question is posed: “Are human beings capable of real altruistic compassion?” One could say that every act which is supposed to be done only to help somebody else, is in reality based on egoism. On could cynically / sceptically ask if Levinas’ ideas aren’t utopian / too far away from reality.

But I am thinking more and more that his ideas are not utopian at all. All “normal” / healthy humans (without a mental illness or handicap) have a conscience. We all distinguish between good and evil. We can have different opinions about what is good and what is bad in certain situations, but our most fundamental feelings about good and bad, and fair and unfair, have big overlaps between people all over the world. These feelings are quite universal I think. I personally have a strong feeling about the things I consider as good / bad and just / unjust in the world, and I can explain why I find a certain situation unfair for a certain group. I can explain why I think that unnecessary harm is being done to them. I can always disagree with other people and we can talk about our disagreements. And my own views are of course only subjective, or at best intersubjective, never completely objective. They always remain my own personal views where other people can disagree with, but that doesn’t matter. I can explain why I see it like that and there will always be some universality in my personal ideas, next to the particularity of my perspective. At least the way I can hear my conscience speak, the way I feel it, that is something which all humans can hear / feel. And my conscience is woken up by the face of the other, who makes an appeal to my responsibility for him. That’s a universal happening, something that already happened before I even noticed what actually happened.

I can see it happen everywhere around me, what Levinas describes, that people are woken up by others and that they are really concerned for the other and that they take their responsibility upon themselves to respond, to open up, to help the other. Of course – unfortunately – the opposite happens just as much, that people look away for the face of the other, that they close their eyes, that they lock themselves up and dehumanize the other.

I can see it happen everywhere around me, what Levinas describes, that people are woken up by others and that they are really concerned for the other and that they take their responsibility upon themselves to respond, to open up, to help the other. Of course – unfortunately – the opposite happens just as much, that people look away for the face of the other, that they close their eyes, that they lock themselves up and dehumanize the other.But I know that real unconditional compassion exists. And it doesn’t matter if personal interests are involved as well, if people want to help others because they feel better themselves afterwards. As long as I really look the other in the face, when I am touched by the appeal of the other and when I sincerely respond to that, then everything is alright.

As I said before, my heart stretches out its arms towards justice. I can only be happy, I can only completely be myself, I can only be at peace with myself, when I listen to my heart and try to move towards justice. You can say that I am selfish that I do my work only because I want to be happy myself, more for that reason than that I really want to help others. But that kind of criticism doesn’t really make sense I think. I don’t do it for status or to become rich or to impress others. I follow my heart and what my heart wants is to really help other people. The happiness that it leads to for me personally is more a by-product, a side-effect.

For me personally it is not so difficult to know what I consider as injustice, and why. When I talk to sheep I can feel that strongly and when I talk to wolves as well. When people are discriminated because of the colour of their skin, or because of their religion or culture, when people dehumanize each other because they see each other as enemies, they hate each other and have forgotten that the others are human beings as well, that’s injustice. When people have no chances at all to go to school or find a job, because they were born in desperate hopeless surroundings, when people die of hunger, who have to fight so hard everyday just to stay alive, or when they die of diseases that could easily be cured if the health services were accurate, when people are being oppressed, derived of their universal human rights, when people are put in prison without having committed a crime, when people are excluded from the society because they are foreigners, all of that is injustice. It makes me happy to do my work because I help those people, people who have such difficult lives and who deserve a better life. With my work I can really do something, I can make concrete improvements.

***

And here are some lyrics that I find very beautiful, lyrics about people who never give up in their struggle for justice, because they have something very strong inside of them and they know that they are not alone. What is so beautiful about it, is that the sheep don't play the victim role here, they fight for their rights and they will never give up. The songs are both related to South-Africa - the land of sheep and wolf - the first is the well-known anti-Apartheid song from Labi Siffre and the second is from Stef Bos, from when he lived in South-Africa. His songs originated from looking at the country while he travelled from north to south, from Mpumalanga to the Cape, "through that never ending land, full of contradictions, a land I started to love more and more". In the CD booklet the song is introduced with the words: " You have to write lyrics with a message of hope. Melancholy is a luxoury only the rich can afford themselves."

Labi Siffre - Something inside so strong

Labi Siffre - Something inside so strong

The higher you build your barriers

The taller I become

The farther you take my rights away

The faster I will run

You can deny me

You can decide to turn your face away

No matter, cos there's....

Something inside so strong

I know that I can make it

Tho' you're doing me wrong, so wrong

You thought that my pride was gone

Oh no, something inside so strong

The more you refuse to hear my voice

The louder I will sing

You hide behind walls of Jericho

Your lies will come tumbling

Deny my place in time

You squander wealth that's mine

My light will shine so brightly

It will blind you

Brothers and sisters

When they insist we're just not good enough

When we know better

Just look 'em in the eyes and say

I'm gonna do it anyway

Stef Bos - You in the dark (translated)

Stef Bos - You in the dark (translated)

You in the dark

You standing in the night

You looking at the sky

And waiting for a miracle

You in the labyrinth

You who has been forgotten

You who searches the light

And who wants to break the chains

You who continues to fight

Against the mills in the wind

Who continues to believe in love

Holding on against the tide

Your are not alone with your thoughts

You are not alone with your dreams

You are not alone standing there

Because we are on your side

4/01/2006

Religion and tolerance

The last weeks I have been reading “ Difficult freedom, essays on Judaism” from Levinas. The essays are very interesting, the book doesn’t explain a complete theory, the short essays are pieces of a puzzle which combine philosophy with religion.

The last weeks I have been reading “ Difficult freedom, essays on Judaism” from Levinas. The essays are very interesting, the book doesn’t explain a complete theory, the short essays are pieces of a puzzle which combine philosophy with religion.Especially the essay “Religion and tolerance” caught my attention, a topic which is very relevant at present (Levinas wrote the book in 1963). The word tolerance nowadays often has a negative connotation, as something old-fashioned which is only promoted by naïve, soft, political correct liberals who lost all sense of reality. In the desire to put a limit to the amount of foreigners who are allowed to enter a country, the first aim is to think of measures to stop as many people as possible from coming to the country. In their tries to avoid problems the government becomes so harsh that they sometimes forget that they are dealing with human beings. There is no ambition to strive for a maximum amount of tolerance, just a maximum of restrictions and rules in order not to be bothered by foreigners.

It is beautiful to see how tolerance is something which is self-evident and naturally for Levinas. He describes the dilemma between tolerance and religion, that with real tolerance you have to accept that other people look at the world in a different way, that what you believe in is not the absolute and one and only possible truth, but that other people believe in other truths, and so that you cannot be not sure that what you believe in is really true and that the others are wrong. Levinas asks himself: “By placing confession in the realm of private opinions as though it resembled aesthetic taste and a preference for a political slant, is it not the case that the modern world here again attests to the death of God?”

This is a big dilemma for Levinas, on the one hand he finds real tolerance, the real acceptance of the other as totally different, very important, but on the other hand he believes that his God really exist, that all that he believes in is true, and that means that when other people have opposed views, that they must be wrong. Conflicting ideas cannot both be true at the same time. Levinas says: “Like the universal truths of philosophers, the believer’s truth tolerates no limits. But it turns not only against every proposal that contradicts it, but also against every man who turns his back on it. Its fervour is rekindled by the burning stake. The most serene truth is already a crusade."

Nonetheless he thinks that it’s possible to combine religion and tolerance. He thinks that tolerance can be inherent in religion without religion losing its exclusivity. He calls Judaism the religion of tolerance. Tolerance is an essential element of Judaism. It is self-evident that we are responsible for how we treat the other, the stranger, we should accept that the other is totally different.

Levinas says: “The welcome given to the stranger which the Bible tirelessly asks of us does not constitute a corollary of Judaism and its love of God, but is the very content of faith. It is an undeclinable responsibility. Before appearing to the Jews as a fellow creature with convictions to be recognized or opposed, the Stranger is the one towards whom one is obliged. The intolerance this entails is directed not against doctrines but against the immorality that can disfigure the human face of my neighbour. "

Levinas says: “The welcome given to the stranger which the Bible tirelessly asks of us does not constitute a corollary of Judaism and its love of God, but is the very content of faith. It is an undeclinable responsibility. Before appearing to the Jews as a fellow creature with convictions to be recognized or opposed, the Stranger is the one towards whom one is obliged. The intolerance this entails is directed not against doctrines but against the immorality that can disfigure the human face of my neighbour. "And my neighbour can be anyone, my family, a friend, but also people I don’t know. The Stranger is also my neighbour. He comes from far and he might need my help, so I am responsible for how I treat him, I should treat him as well as I can. I think it would be very good if Minister Verdonk of immigration affairs would read some books from Levinas, to realise what she is responsible for…

According to Levinas Judaism as a religion doesn’t turn into an imperialist expansion of conversions that devours all who deny it, because it is only directed inwards. “ It burns inwards, as an infinite demand made on oneself, an infinite responsibility.

Levinas describes Judaism in a very positive way, as the religion of tolerance, as the ultimate combination of religion and ethical responsibility. These are of course kind of abstract ideas from Levinas about Judaism. It doesn’t mean that all Jews always act exactly in the way that Levinas envisages this. The reality is always different from an abstract ideal. The Jews are no higher or better human beings because of the nice ideals in their religion (and they exist in other religions just as well). But the ideal that Levinas describes is very good and beautiful. So let’s keep that in mind and let’s strive for that. His ideal is a utopian situation which cannot be fully achieved in reality. But his ideal shows a direction in which we should move, so that we can do the work of justice and come closer to peace and tolerance, as a way to resist against growing intolerance and war. Levinas’ analysis of ethics, humanism, human behaviour, human nature, these are practical and empirical descriptions. We should realise that we are responsible for how we treat the Other, the Stranger. We can know whether we treat him good or bad and we can choose to be good. We will make mistakes sometimes, but if we try our best to be responsible and good human beings it will certainly help. Intolerance should only be against dehumanization. We should never ever forget that the other – no matter who he is – is just as human as me.

Levinas describes Judaism in a very positive way, as the religion of tolerance, as the ultimate combination of religion and ethical responsibility. These are of course kind of abstract ideas from Levinas about Judaism. It doesn’t mean that all Jews always act exactly in the way that Levinas envisages this. The reality is always different from an abstract ideal. The Jews are no higher or better human beings because of the nice ideals in their religion (and they exist in other religions just as well). But the ideal that Levinas describes is very good and beautiful. So let’s keep that in mind and let’s strive for that. His ideal is a utopian situation which cannot be fully achieved in reality. But his ideal shows a direction in which we should move, so that we can do the work of justice and come closer to peace and tolerance, as a way to resist against growing intolerance and war. Levinas’ analysis of ethics, humanism, human behaviour, human nature, these are practical and empirical descriptions. We should realise that we are responsible for how we treat the Other, the Stranger. We can know whether we treat him good or bad and we can choose to be good. We will make mistakes sometimes, but if we try our best to be responsible and good human beings it will certainly help. Intolerance should only be against dehumanization. We should never ever forget that the other – no matter who he is – is just as human as me.